I thought UnderTale would just be a quirky RPG with neat mechanics, but it ended up being a work that brought a lot of positivity into my life.

SPOILERS AHEAD (ALTHOUGH I WISH YOU’D JUST GO PLAY THE GAME ALREADY IF YOU HAVEN’T)

Five years ago, a game came out that took me completely by surprise. I had been watching the game’s progress a few months before its release with some interest. An RPG where no one had to get hurt? I was beyond intrigued with the idea. I mean, I’ve been stabbing goblins and orcs and mad horses for decades, and my body count would probably make me pretty uncomfortable if I thought about it a little too much. As such, the idea of not having to thump monsters to get through an RPG seemed pretty wild at the time. I couldn’t imagine what kind of shape that sort of game would take.

As it turned out, it would take the shape of a silly, laugh-out-loud comedy game. I have played very, very few funny games in my life, and even fewer that managed to make me laugh out loud with its absurd situations, story moments, and characters, but UnderTale had me consistently cracking up. Right from that stubborn rock at the beginning, the game seemed to be teasing gaming conventions and mechanics, and the humor just kept making welcome appearances. The game just didn’t seem to take itself too seriously, making for an experience that had me grinning.

“I think it had a big impact on me because it felt like as you played you got to know its creator. Toby’s personality and humor really shines throughout the game. Made me want to be more expressive of my own humor and tastes in my work.” – Saam Pahlavan

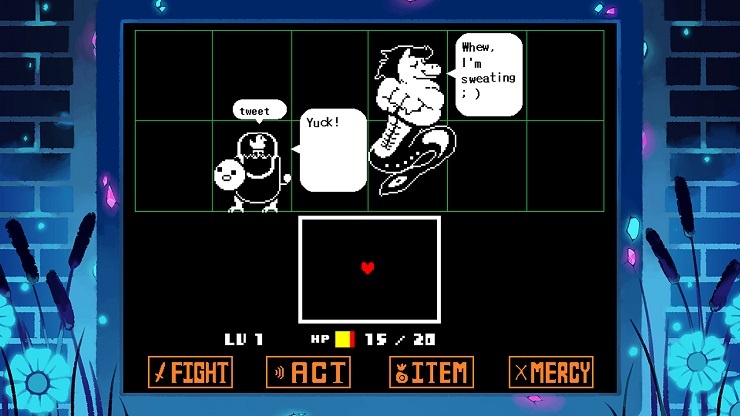

Still, it was that nonviolent mechanic that I’d showed up for, so you’d think I’d have gone out of my way to not hurt anyone right from the start. Unfortunately, I quickly got up to my old habits and started clobbering the creatures I blundered into. I’m not sure why, given that I came to this game to not hurt anyone, but that’s what I did. After a few fights, I did start to feel that I should try out the mechanic that drew me here, finally using the ACT function to see how it would affect a fight. Here, I found more of the game’s characteristic humor as well as a means of chatting my way out of battle.

“What I found inspiring as a game developer was the way the story was told: No large exposition dumps or paragraphs to read through, just one sentence after another that fleshed out characters and the world fantastically.” – Deer Dream Studio

Talking to the monsters, or playing to their quirks and needs, was far more fun that hitting them, as the latter just used the same timing-based attacks, but the former required you to draw from behavioral clues in the monster’s actions to find out what you needed to say to them to end a fight. It asked you to get to know these creatures on a surface level, then use that knowledge to end things peacefully and happily with one another. It’s a feature that I quickly fell in love with, but not one that I firmly accepted just yet.

“It came along at the right time for me, when games like The Stanley Parable were openly playing with being games, but it was also totally sincere and fun in itself. I still think about some of the moments and music, despite never going back for a genocide run. I care too much about the characters to get hung up on completionism.” – Exyoh

It took me getting into a fight with Toriel, the gentle goat mom that helped us through the tutorial-ish section of the game, that I found that I really needed to dedicate myself to learning how to best care for my foes. Because I killed her. I’m hardly the only person who did, but after watching her fade away in a cloud of ash, I felt that I couldn’t let things stand as they had. I’d thought I was meant to kill her – that some monsters you just HAD to fight – but a part of me knew that I’d messed up. So, I reloaded and did the fight again, this time managing to stay alive long enough for her to back off in her assault.

But then I had a conversation with Flowey, the sinister flower that I’d met at the start of the game, and he pointed out that I had killed Toriel, but had reset the game to escape that path.

“Honestly, UnderTale changed my life. It was the first game I ever finished and the game that inspired me to become a game designer. I loved the game so much and how its design kept subverting my expectations. It was the first game that made me genuinely feel responsible for the choices I made, question my decisions, and play with a moral awareness. (Spoiler warning: I felt so bad for accidentally killing Toriel- I didn’t know I could spare her the first time I played- that I played again just to do a 100% pacifist route. I still feel bad for killing her now lol.” – Aims Zhang

UnderTale floored me, here. This, I hadn’t expected. I had never played a game before that had permanence to my actions. If I did anything wrong, I could just go back and erase things of play them again. This title set your actions in stone, no matter how you worked to avoid them. You could erase them to an extent, but your villainy would be remembered.

That sense of permanence would tie in with that feeling of connection with the monsters and characters to create a powerful connection with them. I was comfortable killing RPG monsters, but now that there was a sort of permanence to my actions and bloodthirsty deeds that made these acts seem reprehensible, or at least forced me to internalize how awful I would act while traipsing through a video game world. That the game would have me feel this way while meeting its cast of loving characters, especially our perfect boy, Papyrus, made me feel a harrowing guilt about how I conducted myself in digital spaces.

“UnderTale returned me to this feeling I had as a kid when I would lie in bed and think about what the characters in EarthBound or Chrono Trigger would do after their games were over. What further adventures could they have? How would their lives continue? I don’t want to disturb the world in my UnderTale save file with a reset, and yet I keep revisiting it in my mind.” – Tim Latshaw

The characters felt…real? Maybe that’s not the right word, but their endearing features combined with this permanence and made me want to take care of them. More than that, it gave me this sense that I was responsible for their safety, in a sense. I was basically a dangerous force of nature wandering their lands, so it was myself, as the in-game character, that I had to keep in check. It was that familiar, casual violence I would often inflict on game worlds that I needed to protect them from. I felt connected to them.

This feeling would carry me through multiple playthroughs in rapid succession as I tried to bring everyone home safely, and in doing so, I saw multiple routes through the story open up, creating an ever-more-hopeful world with each attempt. Each time, the characters’ personalities would shine a little brighter, or I’d find some new secret about them that made them even more endearing or complex. I genuinely loved these people more than any character in any medium I’d experienced before. I wanted them to find the best life they could. And eventually, I did.

But I’m a completionist with my games. I like to do every single thing I can when I play. UnderTale still had one more route that I could explore, too. I could kill everyone and everything in a Genocide Run, if I so chose.

“I respect UnderTale immensely for lots of stuff, but one thing in particular: how, when I achieved all I wanted to achieve, and then booted the game up again, it called me out on that. And then I was like “you’re right, little flower demon, what the hell am I doing here?”. Closed the game, never opened it up since then. One of my all-time favorites. Still return to the soundtrack regularly. – Bazukinier

I couldn’t do it. The game makes no bones about you trying to boot it up again after you get the good ending, calling you out on trying to reset this wonderful world you created for the characters. It points out that you’ll be dragging these people back into misery, and when you’re doing that knowing you’re going to be as cruel as possible on this run, it shakes something inside you. At least, it did for me. I shut the game off and let it be, feeling that my actions in this fictional world were too awful to contemplate. I wanted nothing to do with bringing that kind of harm to this world.

Except I would, not too long afterwards, in the interest in writing a book about UnderTale. I had never felt this kind of emotional connection with a work or its characters before. It felt surreal to care this much about fictional beings, but I truly wanted to see them happy and safe from harm. I needed to explore how I felt about them in-depth, spending tens of thousands of words in my search for understanding. Despite all the time I spent on that work, I still find myself having new thoughts about it, too. It’s always stuck with me since I played it.

I haven’t touched it since the book, though. Doing a Genocide Run for my research made me feel like a terrible monster – a genuine hateful thing. The game pulls no punches as you begin to really embrace your cruelty in its world, having your character mercilessly stomp the life out of your foes in the game. It forces you to stare your cruelty in the face as you follow it to its logical conclusion, heading in a disturbing, murderous direction with its plot that I simply wasn’t expecting, but left me shaken. I still feel that guilt now, something that impresses me on one hand, but that doesn’t make the feeling any less horrible. I regret doing it, even if I needed to in order to fully understand the game for the book to be complete. Is understanding really worth it if it hurts so many along the way? It didn’t feel that way for me.

“UnderTale’s message of hope and perseverance helped me through a difficult period. Since then, I’ve made a habit of replaying the game once a year. It reminds me of the things I’ve accomplished (and overcome), and no matter what happens, it’s something I can reliably look forward to doing.” – Kenneth Gagne

Even so, I had written a book and gotten it put out with Storybundle. A published book from me. I never thought I could be capable of that, or that a game would affect me so much that I would put this much time and thought into it. The game had me questioning my feelings on digital spaces and the imagined beings that inhabit them, my own actions when I play through a game world, my perceptions of violence as play or entertainment, and what helps me connect with fictional beings (and to an extent, the real people I love). It had me thinking on how I wished to conduct myself as a human being, and how I could bring more positivity out into the world.

UnderTale made me want to push myself harder in my examinations of games – to think on them in different ways. It made me want to explore more unique works that challenged how we view the medium and what it is capable of, and in doing so it has helped me experience so many wonderful games and stories that I might not have. It lead me to want to champion these kinds of works as best I could, pushing for more compassionate experiences in the gaming space, and for more kindness and understanding in how we conduct ourselves as human beings working this medium.

“I teach high school video game design and it’s a joy to see students who played UnderTale as a kid, which is weird to me but time moves fast these days apparently. The Sans stans really connect with the games themes of optional non violence and connecting with their inner child. So it’s cool to see how it’s this nostalgic, positive game for them which in my bias feels like how I felt about Earthbound when I was their age. It’s not huge with the kids, but it definitely has a little cult following or is a cultural reference point for a bunch of them.” – Aquma

It’s been inspiring to see how the game has affected generations of players as well. It’s incredible to see the positive effects that it’s had on a new generation of players, and the creativity it’s stirred up in them. While some of the UnderTale popularity was undoubtedly overwhelming, the sheer amount of positivity (that I witnessed) involved in it was heartening. Here was a game inspiring wonder and joy in its players, asking them to consider how much their kindness could shape the world around them.

We’re in dire need of that kind of thinking right now, too. The world seems to have been engulfed in hatred and indifference. The people who are fighting against the monstrosities of capitalism run rampant with limitless greed, of the cruelties heaped on minorities, the LGBTQIA+ community, and anyone who doesn’t fit a certain vision of white, straight racial purity have them fighting for their right to simply exist at all times. There’s just so much unnecessary pain out there for so many people that we need to fight back with every ounce of strength in hopes that we can someday create a world where everyone can feel safe and loved in who they are.

“UnderTale is a masterpiece. It’s like Earthbound if it were a Hayao Miyazaki movie: beautiful, strange, interesting, and profoundly unique. It’s a genuine work of art that stays with you long after you’ve completed it. It transcends being just a game, and becomes something like fond memories; memories that you’ll always treasure.” – Jordan Biordi

UnderTale showed me a world where we could make things right through understanding and positivity. It showed me that these kinds of works can bring people together in love and understanding as well, giving me hope that we can steer this world away from the viciousness and heartlessness that infests its ruling classes. It gives me hope, and seeing the courageous actions of protesters around the world, I cannot help but feel that community and love are uniting us like never before. Maybe that’s only because my narrow world-view is only letting me see it now, but building a better world feels possible through the actions of these kind, caring, passionate people.

We need works like UnderTale right now – works where it isn’t our capacity for violence and rage that will save the world, but our actions toward helping one another live with dignity, safety, and love. We need things that are unafraid to show the power of coming together and caring for each other. We need the hope that these works give, rather than endless staring into the darkness for the sake of ‘realism.’ We need to see our world through this lens of positivity, even if it can feel naive, because we need to grab onto the hopeful, better tomorrow that seems impossible anywhere but in our imagination in order to make that place real.

For all of these reasons, I’m endlessly thankful that this game exists, and am happy its lessons in community and connection keep bringing players together. Our lives are quite bleak at the moment, but games like this can be that small bolstering force that keeps the fire alive for a better tomorrow. Our media is what inspires many of us, after all, so something that inspires us to love another with all of our strength is perhaps even more welcome now than it was when it first came out.

The road ahead is still long and lined with cruel forces, but I can only hope that, like in UnderTale, our love for one another will carry us through it.

UnderTale is available on the Nintendo Switch, PS4, PS Vita, the Humble Store, GOG, and Steam.