Our young medium is ever forward-facing. There is so much – both technically and artistically – that hasn’t fully been explored yet. Video games are like a map with lots of white spaces, and how we fill these spaces will shape the future.

On a trip to Switzerland, I visited two schools that try to tackle this challenge, each in their own way.

The Game Technology Center (GTC) is part of the Department of Computer Science of the ETH Zürich. Their aim is to research a way of using games for science and education, and transferring this technology to the game industry. To this end, they are currently exploring Augmented Reality as a playful tool with real-world applications. AR might not be as fancy a technology as VR, but it is easier to implement in an everyday context.

Projects that are currently being worked on are an AR guide for museums that offers a more hands-on experience than an audio guide. It adds interaction to the usually-passive reception of art by allowing you to explore the different stages of restoration that a piece of artwork went through, or adding playful and sometimes funny commentary to other pieces of art.

Another project is an AR coloring book: after coloring a picture, you can scan it in the app and have it come to life in 3D – looking just like you designed it! The aim is obvious: getting children to stop staring at screens all day, while at the same time acknowledging that you can actually do some pretty cool things with those screens.

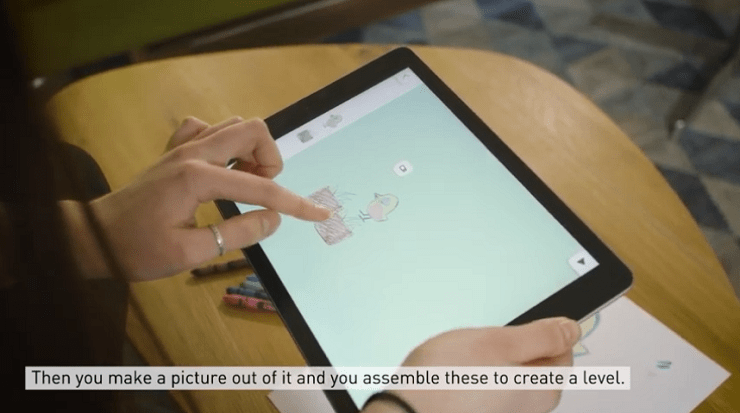

Most impressive might have been a drag and drop game designing tool that makes use of AR. Think of it as the good old Klik & Play construction kit, only that you can take pictures of real-world objects and drawings with your tablet and incorporate them into your game right away. This tool, developed by the team of Dr. Stéphane Magnenat, is surprisingly easy to just pick up and play around with. Creating a fully working Space Invader clone with custom graphics in five minutes? This is how you get kids interested in creating games.

Every year, students of the GTC show off their projects in a big ceremony. Some of these projects attract enough attention for commercial publishing, such as the cooperative railroad building game Unrailed, which recently got picked up by German publisher Daedalic. In any case, the GTC’s approach seems to be in exploring the potential of existing technologies and working your way up from there to create innovative games with real-world applications.

A whole different approach is taught at the other end of the country in Switzerland’s francophone part. A three-hour train ride away from Zürich, at the Haute École d’Arts Appliqués (HEAD) in Genève, students can get a master’s degree in media design. One of the subject’s focal points: games. The school’s approach is notably different to the usual game design education. These students are not game designers in the usual sense; they are designers who happen to make games. They tailor their individual learning experiences to their needs, starting with their project in mind and working from there while teaching themselves the technologies they need. This leads to a variety of wildly different results.

Take Ghofran Akil’s Unresolved, for example. The game, which is her master’s thesis project, deals with the so-called enforced disappeared. These are people who go missing during war and conflict. Following Ghofran’s travels to the Lebanon and interviewing affected families, the project underwent different designs until settling on its final, text-based form.

Unresolved puts you in the shoes of different family members of an enforced disappeared, making decisions that affect the flow of the story. You start as the wife of a disappeared, but you jump back and forth in time during the game, exploring the effect such disappearances have on generations of family members. This is not a game you can win. There is no miracle rescue at the end, no closure for any of the characters. It is a frustrating, ongoing dilemma which affects millions of people today.

Other projects use multi-monitor setups, self-made devices as teaching tools, or they attempt to transfer Swiss literature into gaming form, using a slew of different approaches and tools. Tourmaline Studio’s Oniri Islands, a cooperative tablet game using smart toys, is one of these games that even saw a commercial release. In any case, it is all about the idea at the center of each project, with the particular technologies being of secondary importance.

There are whole branches of game development out there that don’t get a lot of coverage. For these to receive both funding and attention is important. Even if they enjoy less visibility than commercial games, they push our medium forward in ways that may be felt further down the road. Whether these are truly the future of play, the future of interacting with games and gamified programs, or the game designers of tomorrow – all this remains to be seen. What is most important is that games are thriving in all kinds of ways and that the blank spaces on the map are filled with fascinating, varied works.

[DISCLOSURE: travel and accommodation for this trip were paid by Presence Switzerland.]